William Douglas has been writing The Color of Hockey blog for the past eight years. Douglas joined NHL.com in March 2019 and writes about people of color in the game. Today, he profiles John Paris Jr., the first and only black coach to win a professional hockey championship.

John Paris Jr. didn’t fully realize the magnitude of what he had accomplished until it was done.

It didn’t feel like history in the making as the game clock at the Omni hit all zeroes and the Atlanta Knights defeated the Fort Wayne Komets 3-1 in Game 6 of the final to win the International Hockey League’s Turner Cup championship in 1994. Paris entered the history books at that moment as the first black coach to win a hockey championship at any professional level. There hasn’t been one since.

“At the time, you never realize the importance that it can have because you’re in the moment,” Paris said. “I wasn’t there to be the first black [coach] in pro hockey, I was there because I was offered a position. Later on, I realized I opened a door.”

It’s a door that only a few have walked through since. Dirk Graham, who became the NHL’s first black captain with the Chicago Blackhawks in 1989, became the League’s first and still only black coach when he guided the Blackhawks for 52 games in 1998-99.

Leo Thomas, the uncle of Los Angeles Kings prospect Akil Thomas, became the first black coach in the Southern Professional Hockey League when he was hired by Macon in May 2018. He was fired in November 2019.

Graeme Townshend, the NHL’s first player born in Jamaica, coached Macon’s Central Hockey League team in 1999-2000. Ironically, he succeeded Paris, who coached the team from 1996-97 to 1998-99.

“I don’t think people understand that what John did in Atlanta, how important it was,” said Dave Starman, a hockey analyst for NHL Network and CBS Sports Network who coached under Paris at minor league stops in Atlanta and Macon. “What he overcame, physically plus being a person of color to come through in this sport, I do think he sometimes gets forgotten about and he shouldn’t. He’s one of the more unique human beings I’ve ever been associated with.”

Paris believes that more coaches of color are on the way in the near future thanks, in part, to initiatives such as the NHL Declaration of Principles, which seeks to provide a safe, positive and inclusive environment in hockey regardless of race, color, religion, national origin, gender, age, disability, sexual orientation and socioeconomic status.

He said Commissioner Gary Bettman’s announcement at the NHL Board of Governors meeting in Pebble Beach, California, in December to accelerate a strategic plan focusing on culture and inclusion in hockey will also help. Commissioner Bettman outlined the plan in response to allegations regarding alleged abusive behavior from certain coaches, initially brought into focus by former NHL player Akim Aliu.

“Gary Bettman, I’ll tip my hat to him and to the National Hockey League, because they did not sugarcoat it,” the 73-year-old Paris said. “Right away, they sent a message — it was very clear. And they started earlier with zero tolerance.

“By doing that and taking a stance, now it’s opened up the doors. I think the future is great because there are more black, brown, Asian youths playing hockey. There are more who are coaching youth, assistant coaches out there. They’re not there, but they’re getting there.”

Mike Grier is in his second season as an assistant with the New Jersey Devils; he’s one of the few NHL assistants of color who works behind the bench during games. Jason Payne has been an assistant for Cincinnati of the ECHL since 2018. Kahlil Thomas, Akil’s father, is an assistant with Greenville of the ECHL.

At the college level, Paul Jerrard, a former Calgary Flames and Dallas Stars assistant, joined the University of Nebraska-Omaha coaching staff in May 2018; Leon Hayward has been coaching at Colorado College since 2017; and Duante Abercrombie, who played for U.S. Hockey Hall of Famer Neal Henderson’s Fort Dupont Ice Hockey Club, is an assistant at Stevenson University, an NCAA Division III school near Baltimore.

Paris grew up in Windsor, Nova Scotia, where he developed into such a talented player that a young Montreal Canadiens scout named Scotty Bowman (who became the winningest coach in NHL history and won the Stanley Cup nine times) paid his family a visit in May 1963. Paris tried out for the Junior Canadiens and found himself on the Montreal Forum ice with the likes of future NHL players Jacques Lemaire, Carol Vadnais, Serge Savard, Andre Lacroix and Christian Bordeleau.

At 17 years old and weighing about 135 pounds, Paris didn’t make the team. Instead, he played the following season in the Metropolitan Montreal Junior Hockey League with the Maisonneuve Braves. His skating and scoring prowess there earned him the nickname “Chocolate Rocket.” He climbed hockey’s ladder and made it to the minor leagues, playing nine games in 1967-68 for Knoxville in the old Eastern Hockey League.

Hodgkin lymphoma and ulcerative colitis effectively ended Paris’ playing career. Once his health improved, he began coaching youth hockey and became the Quebec Major Junior Hockey League’s first black coach with Trois Rivieres in 1987-88.

But coaching in the province where Jackie Robinson played before breaking Major League Baseball’s color barrier in 1947, wasn’t easy. Paris was spat upon by fans, had coins thrown at him and racist epithets directed toward him.

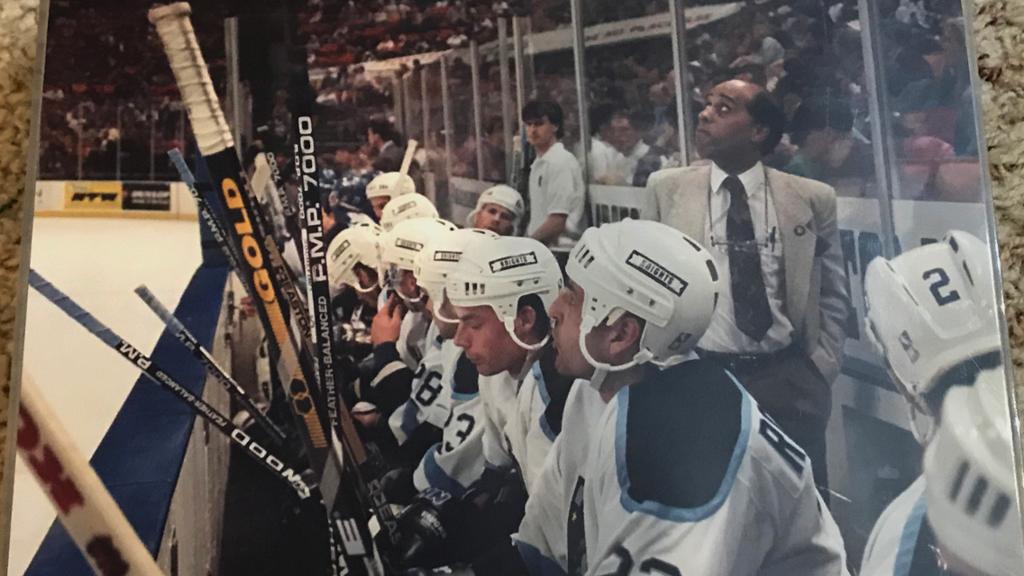

He was tapped by Atlanta management in February 1994 to coach the IHL team after being originally hired to lead the ownership group’s roller hockey franchise. Instead, Paris replaced coach Gene Ubriaco, who was moved to a pro scouting position by the Tampa Bay Lightning, the Knights’ NHL parent club.

When asked if he was worried about having black man coaching in a southern city, former Knights co-owner Richard Adler told The Gwinnett Daily Post that he initially didn’t know Paris was black — and he didn’t care.

“He was a Canadian, as far as I knew, and if he was good enough for Scotty Bowman, he was good enough for me,” Adler told the Daily Post. “It really worked out well.”

Paris said he did receive some hate mail in Atlanta but chalked it up to out-of-towners.

“I was well-treated by the fans in Atlanta,” he said. “Most of the problems I had were from other states that weren’t in the South, the hate mail and that.”

The hateful messages didn’t seem to bother Paris, said Brent Gretzky, who was a Lightning prospect on the Knights.

“He never brought attention to himself or ‘Hey, I’m the black coach here,'” the younger brother of NHL all-time scoring leader Wayne Gretzky said. “He was just another cog in our wheel on the team that made us better. The way he handled it was perfect.”

Starman said Paris wanted to be judged on his coaching skills.

“I don’t think John ever wanted to make race an issue,” he said. “I think what John wanted people to know about him was that he was a [heck] of a coach, and he was. He really taught the game. I go back a lot when I coach, whether its kids or juniors or whatever the case was, there’s a lot of stuff I picked up from John that is still applicable in today’s game when it comes to relating to players.”

Paris said that low-key approach was part of the way he was raised. He said he’s a coach by choice and black by nature.

“When I was brought up,” he said, “you were supposed to learn from the past and use that simply as a motivator and use that as a better track for the future and the present.”